- eperper@sciencebranding.com

- Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the

Stop guessing why some choices make you happy and others don’t

18 years of research across psychology, neuroscience, and philosophy reveal four pairs that explain every decision you make. Learn to recognize them in 90 minutes.

You make thousands of choices daily. Many feel random. Some bring lasting satisfaction. Others bring regret. The difference isn’t willpower. It isn’t positive thinking. It’s a pattern. The Four Pairs framework shows you the exact mechanism connecting what you do now to how you’ll feel later. No affirmations. No habit stacking. One structure that explains why you repeat the choices you regret.

A New System That Reveals WhatDrives Happiness and Unhappiness

Not Motivation. Mechanism.

You don't need another pep talk. You need to see the structure behind your choices.

No Tips. A Framework.

Tips expire. A framework works for every decision you'll face for the rest of your life.

Not Positive Thinking. Pattern Recognition.

Happiness isn't about attitude. It's about seeing the four patterns before they play out.

90-second Summary

The Framework

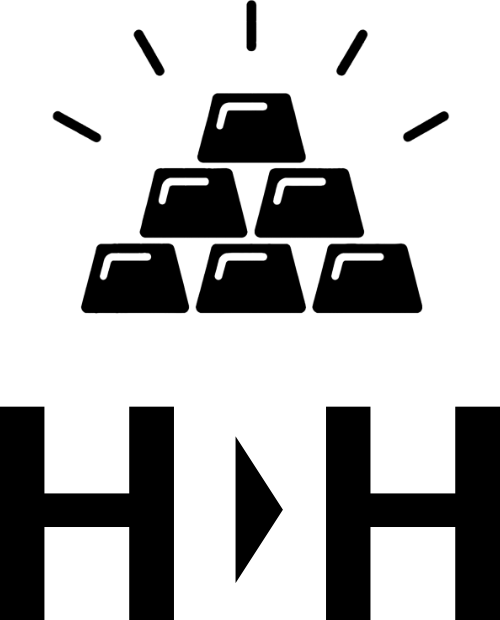

The Idea Behind the Four Pairs

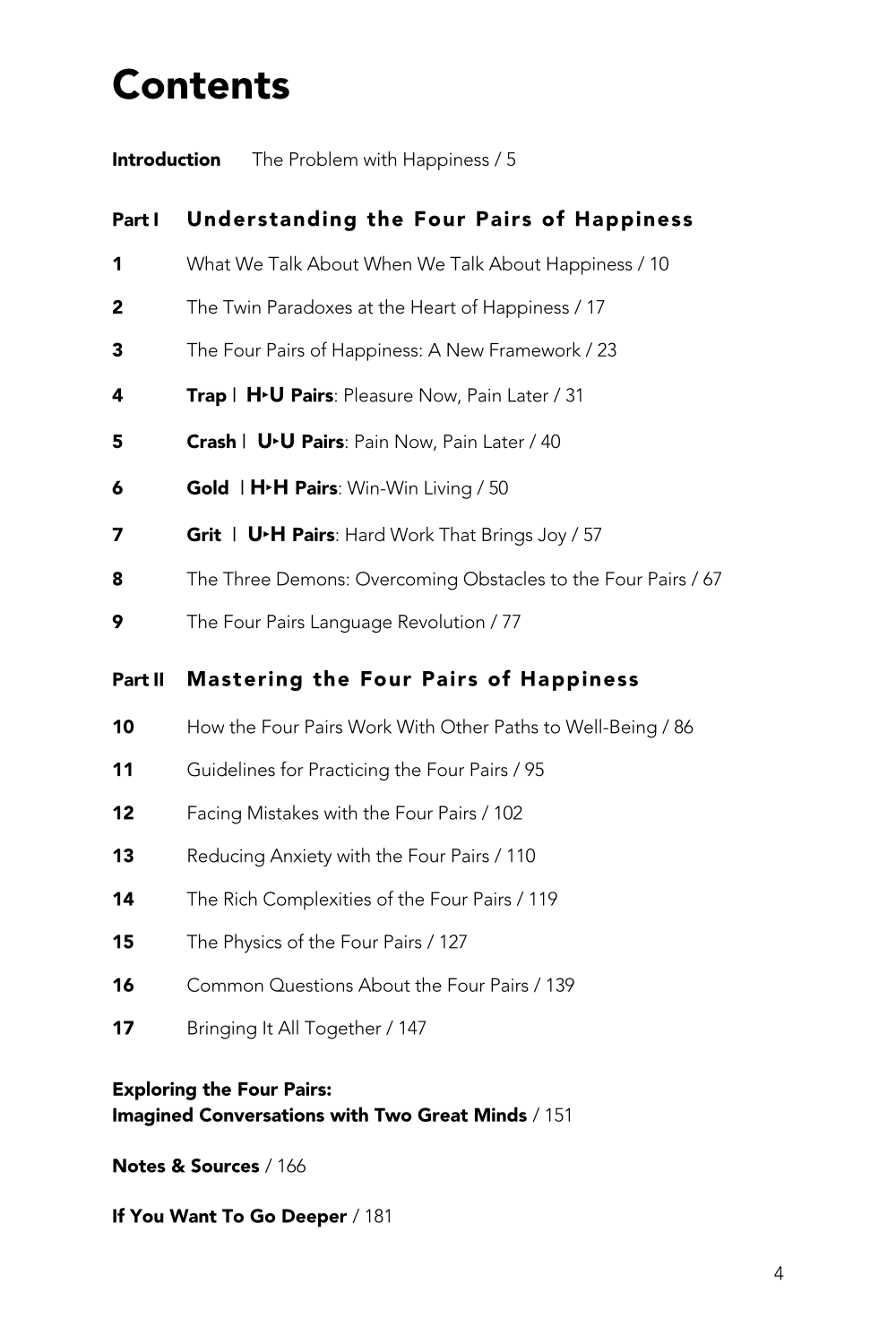

Most choices in your life fall into one of four patterns (pairs).

Happiness now ▸ Happiness later

GOLD: When you enjoy the present action (eg, meditating) and it brings more benefits in the future (eg, tranquility).

Unhappiness now ▸ Happiness later

GRIT: When you engage with a difficult task (eg, exercising) to achieve positive results in future (eg, fitness).

Happiness now ▸ Unhappiness later

TRAP: When you enjoy an activity in the present (eg, TV binging) but it causes problems in the future (eg, missing deadline).

Unhappiness now ▸ Unhappiness later

CRASH: When you do something unpleasant (eg, lifting weights) and it causes more problems in future (eg, strained back).

Inside the BookExplore Selected Chapters

Peek into seven selected chapters to understand the Four Pairs, spot the traps, then master the practice rules.

The book demonstrates that people frequently seek surface-level elevation without considering how their decisions influence future emotional states. This results in cycles in which short-term emotions subtly erode long-term balance.

The framework highlights two fundamental contradictions: what feels wonderful now may not support what follows later, and what feels tough now may lead to better conditions in the future. These competing forces explain why inner states can be confused.

This pair refers to behaviors that feel pleasant in the moment but cause strain over time. The book demonstrates how these choices gradually lead people away from the life they truly desire.

This pair focuses on behaviors that, while initially difficult, result in better long-term benefits. The book demonstrates how following these approaches leads to a more secure and grounded inner state over time.

The Four Pairs framework organizes, rather than replaces, different personal improvement strategies. It helps people understand which choices promote long-term balance and which subtly undermine it.

The book lays forth clear guidelines for determining which pair a decision belongs to before acting on it. This enables readers to make more informed judgments and experience fewer future regrets.

The idea presents emotional patterns as forces that move a person forward or backward over time. Understanding of these UH patterns encourages readers to foresee where their decisions will take them.

About the Author

Edward Perper, MD

Edward Perper, MD, is a Harvard and Stanford-trained cardiologist who built two medical education organizations. For 30 years, he taught doctors how to explain complex ideas clearly. He spent 18 years studying over 1,000 research papers on happiness, well-being, and decision-making. The Four Pairs framework is the result: a simple structure that connects everyday choices to long-term satisfaction. He lives in Southern California with his wife Leslie.